Despite the Brexit trade deal clinched on Christmas Eve, businesses across the UK have quickly discovered that many of them must now pay duties on exports bound for the EU. The development is part of trade disruption that has become increasingly evident this year after Britain’s divorce from the bloc was finalised on December 31. Trade has also been badly hampered by new coronavirus border restrictions, with the roll-out of testing for lorry drivers, as Britain races to curb a rampant variant of the deadly virus.

At the heart of the Brexit deal, which came into force on January 1, is the so-called “rules of origin” condition applied to all goods crossing the border.

The rules of origin, a key aspect of all major trade deals, can rapidly turn into a costly headache for businesses.

Under the Brexit provision, any goods will be subject to a customs levy if it arrives in Britain from abroad and is then exported back into the EU.

If a British clothing retailer imports Chinese-made textiles, for example, then it would have to pay a customs charge if it re-exports the items into a member nation of the EU’s single market and customs union.

Put simply, the rules therefore determine whether an export is considered British or not.

Raoul Ruparel, who advised former Prime Theresa May during her Brexit negotiations with the EU as part of his role with Deloitte, blamed the disruption on the EU.

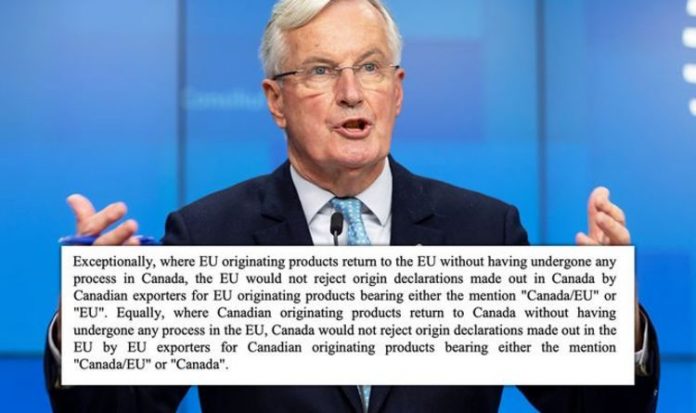

Mr Ruparel argued that a facilitation for rules of origin was granted to Canada in CETA but not to Britain.

He explained on Twitter: “As I and others have said, a lot of the disruption we are seeing is the result of the fact that the UK and the EU went for a free trade agreement (FTA) rather than another form of relationship.

“However, there is an interesting point on rules of origin, where a facilitation included in CETA was not included in the UK deal.

“Under CETA a product exported from one party to the other then returned without any processing can still qualify for preferential tariff on return. But it can’t under the UK deal.”

He noted that one of the challenges businesses are facing is that products moved from the EU to the UK and then back to EU are no longer eligible for preferential tariffs even if they haven’t undergone processing.

Mr Ruprael added: “While there are ways around this – using transit, customs warehouses or returned goods relief – they are more complicated than the simpler process found under CETA.”

JUST IN: EU Commission bends retirement age rules to give Barnier Brexit job

Explaining why this was not included in the EU-UK trade deal, the former adviser said: “I tend to think it was a deliberate decision to avoid the UK becoming a distribution hub for the EU or something along those lines. However, it does have a very acute impact on Ireland.

“This sort of process would make it much easier to move things across the GB land bridge into Ireland. We’ve seen reports Irish government are discussing rules of origin with the EU, I’d think this is precisely the sort of processes/facilitation they should be pushing for.”

A facilitation for rules of origin is not the only thing the EU supposedly denied the UK in their trade agreement.

According to Government trade adviser Shanker Singham, Brussels refused to do a “mutual recognition agreement” with London on Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures (SPS).

As it stands, New Zealand appears to have a closer relationship on SPS with the EU than Britain, with an agreement that limits checks and simplifies paperwork.

Mr Singham, the CEO of economic consultancy firm Competere, told Express.co.uk: “New Zealand and the EU have a veterinary agreement on meat products, which is actually a very good agreement.

“It is a mutual recognition agreement of underlying product regulation.

DON’T MISS:

EU Commission bends retirement age rules to give Barnier Brexit job [REVEALED]

Blair, Clegg and Major met with EU leaders to stop UK’s withdrawal [INSIGHT]

SNP’s independence bid crushed: ‘Don’t even have money for buses’ [EXCLUSIVE]

“So, even though New Zealand and the EU have different SPS regimes for meat, they recognise each other’s underlying product regulation.”

The trade expert noted: “So much for the view that the EU doesn’t do mutual recognition… it does.”

According to Mr Singham, there is no reason why Britain cannot have the same agreement with the EU.

He added: “If you do that with New Zealand, which has got a different SPS regime, why would you not do that with the UK, which at the moment has got the same?

“Pretty absurd the EU did not put that in… it’s a very political move and it made no sense.

“But anyway, we will be negotiating such a thing in the future.

“We have a roadmap.

“So it will be quite easy for us to negotiate a similar agreement.”

New Zealand is recognised worldwide as a reliable SPS partner.

The New Zealand veterinary agreement, signed in 1996, provides for the recognition of the legislative controls applied to animal diseases by trading partners.

This reduces the compliance costs of New Zealand’s industry meeting requirements such as animal health certification assurances, and contributes to improved market access for the country’s products to Europe.

It also recognises meat and dairy inspection systems in New Zealand as equivalent.