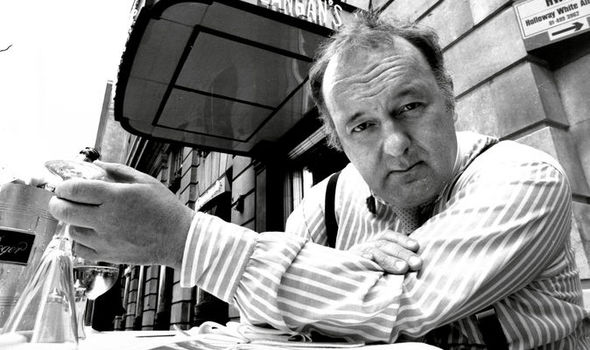

Peter Langan was a man of uncertain temperament and a permanent raging thirst (Image: Chris Barham/ANL/REX/Shutterstock)

Princess Diana went there, so too did Princess Margaret, Princess Michael of Kent, Princess Caroline of Monaco.

Yet two tables away there could be a hen-party of shop assistants – no wider social mix ever gathered under one roof than at Langan’s in its heyday.

But now, after 44 years, the party’s over. Coronavirus has taken its revenge, the doors have shut, and the legend has been swept away.

Just steps from London’s Piccadilly, the restaurant’s opening in 1976 single-handedly spawned the birth of the paparazzi, and that night the Age of Celebrity dawned.

The man who stood front and centre, in his crumpled white suit and battered co-respondent shoes, was former petrol salesman and professional Irishman Peter Langan – a man of uncertain temperament and a permanent raging thirst.

Behind him stood actor and investor Michael Caine and gifted chef and restaurateur Richard Shepherd.

Without these two, Langan’s would have been nothing – but without Langan, there would have been no legend.

He’s remembered today as society’s great ringmaster – a man for whom Wayne Sleep once danced naked across the tablecloths, a man who labelled Dudley Moore the “house pianist” and David Hockney the “house painter”.

A man who, when there was a fire in the kitchen, put it out with Moet & Chandon champagne. And when somebody complained about finding a cockroach under the table, scooped it up and swallowed it whole, washing it down with vintage Krug. A man who bet a fiver with Shell heiress Olga Deterding that she wouldn’t sit naked in his window all afternoon. She did.

When Princess Diana came to dinner he invited himself to her table, then promptly fell asleep. He went on a five-day foreign bender with the painter Francis Bacon and, on his return, put himself through the luggage carousel at Heathrow Airport.

Princess Diana was among the prestigious guests found dining at the brasserie (Image: Getty)

And he drank champagne like there was no tomorrow, claiming his daily intake was seven bottles.

With his celebrity customers he could be astonishingly rude – he once asked Princess Margaret, “And how was the ******* dinner, Ma’am?”, and staff remember he had to be physically restrained from goosing the royal rear as she left.

Yet it was Langan’s unique genius that he could speak and act offensively, yet not cause offence. Margaret became a regular.

Langan knew the “grown-ups” understood it was all an act – a piece of outrageous showmanship designed to create headlines – and they put up with it.

He bought them drinks and laughed his raucous laugh. But for lesser souls, timid customers who’d saved up their pennies to come and rub shoulders with the rich and famous, Langan’s was a once-in-a-lifetime experience, and to them he was always courteous, generous and mild-mannered.

He had set out to make his a brasserie along French lines, where all were welcome – famous or not.

Langan was a Marmite figure – you loved him or you hated him. I loved him – I sat often in his restaurant doing my best not to let him buy me drinks because I knew what his colossal generosity was doing to the restaurant’s balance-sheet.

Downstairs in the kitchen, the man who made everything go like clockwork – Michelin-starred chef Shepherd – was not only hardworking and shrewd but a saintly figure, having every morning to look at the books and see how much of the takings Langan had blown the previous night.

How he put up with him nobody knew. His fat Irish partner could be found curled up at lunchtime, fast asleep under the restaurant’s grand piano, or he might wander in having spent the night sleeping in a skip because he was too drunk to find his way home.

All these stories, of course, crept into the gossip columns and kept Langan’s Brasserie the most sought-after dinner venue in Britain. But behind the braggadocio was a complex animal driven by fathomless demons. Part of it was guilt – Langan may have become the king of Mayfair, but he came from a poverty-stricken village in the west of Ireland where many homes had earth floors, children walked to school barefoot and ate dry bread for their lunch. Only his father and the local doctor owned a car.

Joan Collins at Langan’s brasserie (Image: Richard Young/REX/Shutterstock)

The noisy persona shielded a personal shyness which derived from being the child of two impossible parents. Peter’s mother was “cold as an iceberg”, a neighbour once told me. His wife Susan once asked him if he’d ever been hugged as a child. Langan snapped back, “You must be joking”. He escaped to England as soon as he could.

Improbably, London’s most successful restaurant was inspired by a humble ex-transport café in Cornwall. Its owner, Auguste Solamito, had worked at The Savoy and other top-notch establishments but by the early 1960s wanted his own place.

Solamito brought his London gloss to the backstreets of Truro and, with natural showmanship, started attracting attention to himself and his establishment by creating a “top table” in the cramped premises, an upstaging ploy his protégé was later to copy.

The man who in a few short years would rub shoulders with Mick Jagger and Elton John was at the time an unsuccessful petrol salesman, dumped in the West Country by employers who got him out of the way before finally sacking him for incompetence.

Langan ate at Solamito’s three or four times a week, learned the trade, and finally made his appointment with destiny.

In a few short years he came, he saw and he conquered the London restaurant world – forging a path for later bad-boy chefs like Gordon Ramsay and Marco Pierre White who would trail in the footsteps of his notoriety. But soon Langan hankered after bigger things.

Not content with the fact that his London restaurant was now the go-to establishment for the international jet-set, he set himself the target of opening up in Los Angeles.

Michael Caine told me: “I begged him not to. I got down on my knees in front of everybody in the brasserie and said, ‘Please, Peter – don’t do it’.”

Caine explained that while Londoners had a sense of humour and could put up with a drunken Irishman nibbling their ankles while they tucked into their anchovy soufflé, in Tinseltown – where everybody takes themselves far too seriously – celebrity diners would be aghast.

Models Marie Helvin and Jerry Hall party at Langan’s (Image: Alan Davidson/REX/Shutterstock)

Caine was right. I flew with Peter to LA to look at the spacious premises he’d earmarked on a corner of La Cienega Boulevard. We went up to David Hockney’s house in the hills. We drank with Dudley Moore, had tea with Roger Moore. All seemed set fair.

But half-a-million dollars later, Peter found he’d alienated his investors with his drunken Irishman act, and he was forced to downsize to a less fashionable site.

Even then, the curse which now dogged him wouldn’t let him go – the night Langan’s LA opened, he was banned from the premises. Drunk again.

It was no better back at home, where his behaviour became so unreasonable Caine and Shepherd asked him to stay away from the restaurant which bore his name. And this was not his final humiliation – he got banned from the pub near his home in Essex, at the same time discovering other Langan’s offshoot restaurants he’d set up were failing to prosper.

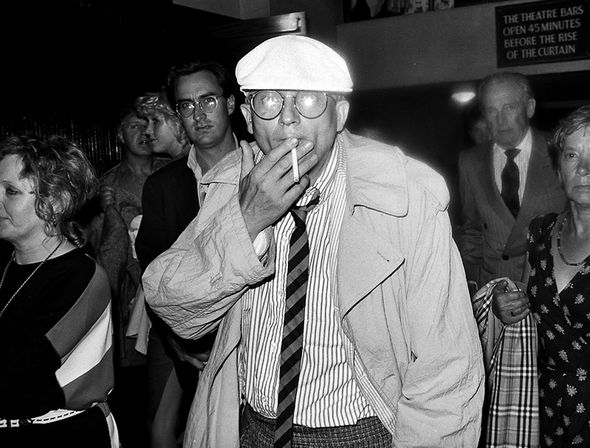

Artist David Hockney at the iconic brasserie (Image: Alan Davidson/REX/Shutterstock)

The one shining light in his life was his poised and elegant wife, Susan, whom he had met when she was a temporary waitress at his first London bistro many years before.

Amused but far from overwhelmed by her husband’s colossal celebrity, Susan chose to keep well away from the mad circus he’d created and was the one constant, stabilising, thing in his rapidly disintegrating life.

“Susan was where Peter would go to hide,” said his friend Mike Aalders years later.

Friends marvelled at how she tolerated Peter, who by now had given in to alcohol and could be found drinking strawberry daiquiris at breakfast.

Inevitably she fell in love with another man, and Langan, all too recently London society’s great ringmaster and Britain’s most famous restaurateur, was fearful of losing the one thing he truly treasured.

He set fire to his house, and to himself, dying at the impossibly young age of 47 in 1988.

Langan’s Brasserie, his great invention, lived on. His partner Shepherd eventually became the sole proprietor, skilfully guiding the establishment to a record-breaking 44 years’ trading.

Coronavirus shut the place earlier this year, but in truth the magic created by the impossible Irishman had long gone – it needed his wickedness, his outrageousness, and without his noisy presence the glamour simply faded away.

Now administrators have been called in and the future is bleak. For Langan’s, alas, the party’s finally over.

- CHRISTOPHER WILSON once wrote Peter Langan’s biography but, hit by the curse of Langan, the publishers went bankrupt before it could be published