The EU’s chief Brexit negotiator Michel Barnier has urged member states to come up with a compromise on fishing rights to present to Britain, as trade talks reach their most delicate phase. The advice was made at a meeting of member state envoys on Wednesday, in which Mr Barnier also insisted Brussels will hold firm on negotiation priorities such as state aid and the governance mechanism of the final deal. Fishing rights are a main concern for countries sharing seas with Britain: the Netherlands, Belgium, Denmark, Germany and especially France, which has taken the toughest line on the issue.

Mr Barnier told the envoys: “If we want an agreement, we will also need to find agreement on fish.

“We need a compromise that we would float to the UK as part of a total agreement.”

In negotiations, the European side has so far insisted that its vessels would continue to enjoy unfettered access to UK waters, even after a post-Brexit transition phase that ends on December 31.

However, Britain wants this access limited significantly and has called for fishing rights in its waters to be renegotiated every year, a demand that according to sources close to the talks, the EU will refuse.

A diplomat said: “Mr Barnier believes the EU must prepare itself for a reduced access to British waters.”

EU discussed 1666 treaty as desperate bloc tries to settle Brexit fishing row (Image: GETTY / WIKI COMMENTS)

EU’s chief Brexit negotiator Michel Barnier (Image: GETTY)

It appears, though, that EU leaders might have an ace up their sleeve as an ancient treaty that could make a mockery of his efforts to take back control of the seas has been recently brought up.

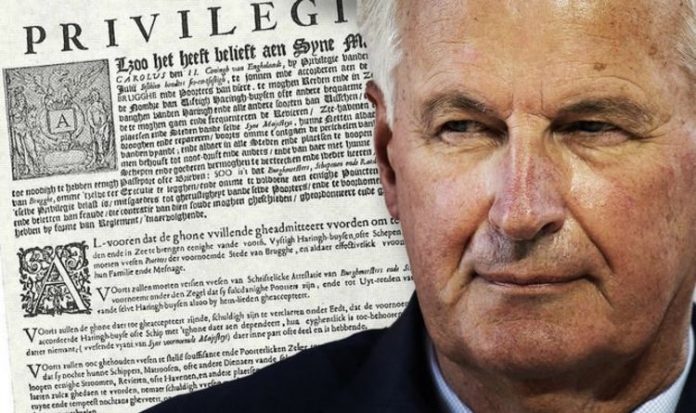

The Financial Times’ Brussels correspondent Jim Brunsden wrote on Twitter: “It turns out that, in 1666, King Charles II gave 50 fishermen from Bruges the right to access UK waters ‘for eternity’.

“Belgium brought it up at COREPER yesterday.”

However, Mr Brunsden noted: “Just to be clear: this came up in COREPER as a historical curiosity, it is not – to the best of my knowledge – some cunning new EU negotiating strategy to hark back to the Restoration of the Stuarts.”

Flemish politicians are in possession of a 350-year-old royal charter, which grants “eternal rights” to Belgian trawlermen to fish in British waters, even after Brexit.

King Charles II signed the “privilege” on October 2, 1666.

JUST IN: Brexit breakthrough as solution to state aid row unveiled

Prime Minster Boris Johnson (Image: GETTY)

British fisherman (Image: GETTY)

Charles signed the treaty to express his gratitude for being granted refuge in Bruges during the Interregnum, having been driven from Britain in 1651 by Oliver Cromwell.

He regained the throne in June 1660 and was determined to thank his sympathisers from the Cromwell years thereafter.

Geert Bourgeois, the ex-Prime Minister of the Belgian region of Flanders said in 2017, that the “fisheries privilege” granted 50 fishermen from Bruges access to British waters “for eternity”.

Speaking to Flemish TV, he unearthed a copy of the document, which was discovered in 1963 in Bruges’ archives.

He suggested that the British would be afraid it could be legally enforceable.

It is not clear whether the terms of the treaty would still apply today.

Spokeswoman for Mr Bourgeois, Lisa Lust, told The Telegraph that Britain had shied away from testing the legality of the “privilege” in 1963, one year before the London Convention was agreed.

A Bruges alderman ventured into British waters, she said, and deliberately had himself arrested in the hope of being taken to court.

She noted: “Documents from the British archives later revealed that it was advised against taking the Belgian to court because of fears concerning the 1666 charter.

DON’T MISS:

500 Whitehall officials earn MORE than £150k a year [ANALYSIS]

Sturgeon’s vendetta with Salmond could blow nationalists apart [INSIGHT]

Finland threatens Brussels with bombshell EU referendum [REVEALED]

The Royal Charter (Image: WIKI COMMENTS)

“They were afraid it would still be in force.”

Ms Lust admitted the chances were small but that it was “not completely impossible” the charter grants Bruges fishermen some rights.

Moreover, Antwerp University history professor Luc Duerloo told The I: “In theory, such privilege can only be undone if Parliament explicitly approves a law.

“That’s never happened, so in principle the privilege still applies.”

During his stay in Bruges, Charles was an active member of civil society and became a member of the Saint Joris Guild, through which he made some strategic friendships.

Once he regained the throne in England, his earlier guide and friend in Bruges, the knight Arrazola de Oñate was named “exceptional” ambassador to Charles by the Spanish King Philip IV with the intention to negotiate a trade treaty.

Although the treaty has been lost, the City of Bruges still possesses the charter granting privileges to its fishermen to fish in English waters.

The charter was never really tested until 1851 due to the numerous conflicts that affected Europe between its signing and the mid-19th century.