BERLIN — Germany’s steadfast approach has made the country a model for combatting the coronavirus, but that success is helping to spread another ill across German society: pandemic denial.

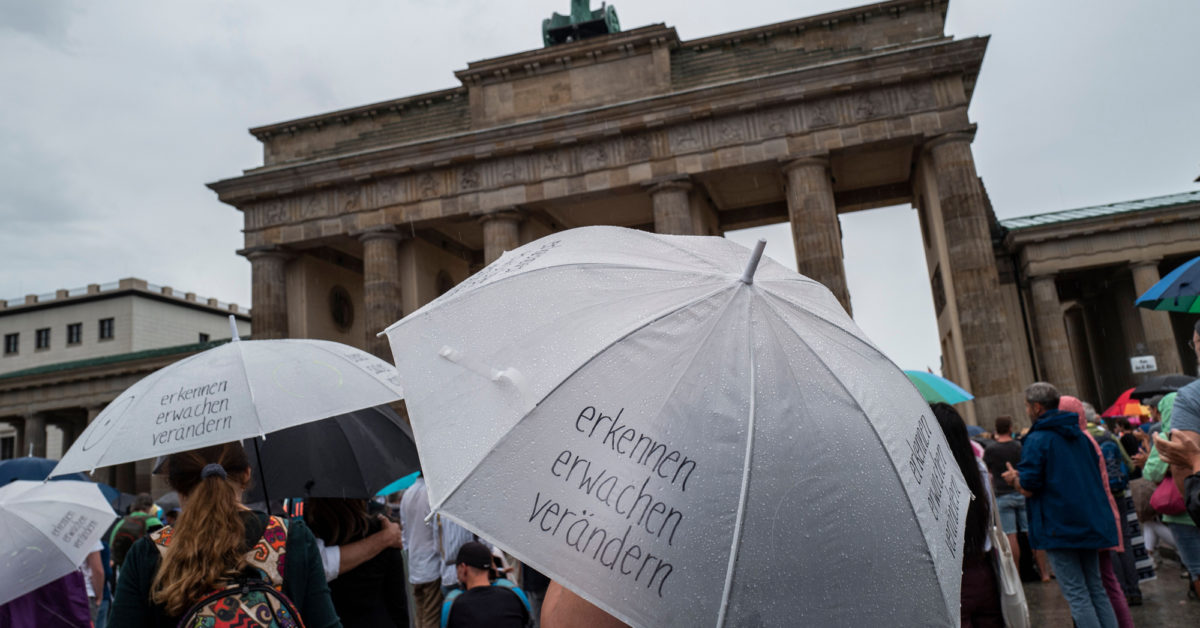

A mass demonstration in central Berlin over the weekend that drew an estimated 20,000 protestors underscored the allure of Germany’s burgeoning coronavirus-denial movement, a motley group whose adherents span the political spectrum. Saturday’s marchers included everyone from neo-Nazis waving the Reichsflagge (a symbol of the German Empire displayed by many on the extreme right in lieu of the banned swastika) to dreadlocked peace protestors and LGBTQ activists carrying rainbow banners. Hardly any of the protestors, who accuse the government and press of lying about the pandemic, wore masks or followed social distancing rules, prompting authorities to put an early end to the demonstration.

The potency and political breadth of Saturday’s demonstration (dubbed “The end of the pandemic — day of freedom,” by its organizers) rattled political leaders.

“The scenes we were forced to witness are unacceptable,” a spokeswoman for Chancellor Angela Merkel said on Monday, adding that the demonstrators had misused Germany’s constitutional right to protest to flout public health warnings.

“The irresponsibility of a small few poses a risk for us all,” President Frank-Walter Steinmeier warned in a video statement. Though Germany, a country of more than 80 million, has fared well during the pandemic compared to most large countries (some 9,200 people have died of COVID-19), authorities are bracing for a second wave and, as elsewhere in Europe, are already seeing signs of a resurgence.

Even if relatively few Germans have been confronted with COVID-19 up close, they are feeling the economic pain the pandemic has wrought.

Those efforts could be complicated, however, if the kind of skepticism over the severity of the virus that pervaded the weekend protest takes deeper root.

Germany’s experience underscores the challenge governments that have managed to keep infection rates depressed face in convincing their citizens to remain vigilant and comply with restrictions without appearing to infringe on civil rights.

If, for example, German authorities had refused to allow Saturday’s protest on public health grounds, anticipating that the coronavirus deniers wouldn’t wear masks, they would have been accused of quashing a legal protest.

Economic pain

Even if relatively few Germans have been confronted with COVID-19 up close, they are feeling the economic pain the pandemic has wrought. Germany’s economy contracted by more than 10 percent in the second quarter, outpacing the decline in the U.S., and unemployment has soared with more than 500,000 people losing their jobs since the beginning of the pandemic. Nearly 7 million Germans have been placed on Kurzarbeit, a government-supported program that keeps workers on company payrolls, albeit with a reduced salary.

Even if Germany’s economy looks robust compared with the likes of Spain and Italy, many German workers are experiencing the worst conditions they’ve ever seen, prompting many to second-guess the government’s strategy for combatting the pandemic.

And though most Germans don’t subscribe to the conspiracies peddled by the groups protesting on Saturday, many say that the government’s response to the pandemic was overdone. One-fifth of Germans believe that politicians and the media have intentionally exaggerated the danger posed by the coronavirus in order to mislead the public, according to a study conducted in May by infratest dimap, a leading German polling institute. Among respondents who described themselves as “active users” of digital media, the figure ascribing devious motives to politicians and media was over 30 percent.

So far, the only political party to champion the coronavirus skeptics has been the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD), many of whose supporters joined the weekend march. AfD leaders have tried to cast themselves as defenders of German civil rights, for the most part avoiding a scientific debate over the severity of the pandemic.

“It’s laudable that so many people took to the streets of Berlin to demonstrate for their civil rights,” AfD co-leader Tino Chrupalla told German public television on Tuesday.

There’s no evidence that the party has benefited from its flirtation with the deniers, however. If anything, the pandemic, which has coincided with a spate of infighting in the AfD, has eroded trust in the populist party, which has seen its support fall to just 10 percent from 14 percent at the beginning of the year, according to POLITICO’s Poll of Polls.

Indeed, despite the controversy surrounding the demonstration, a clear majority of Germans still supports the COVID restrictions and even endorses sanctions for those who break the rules. Nearly 80 percent of Germans favor fines for people who flout coronavirus rules, according to a YouGov poll published on Monday.

The results suggest that the government’s strategy of branding the pandemic deniers as reckless, or “covidiots” as a leading Social Democrat put it, is working.

The only question is for how long.

The post German coronavirus deniers test Merkel government appeared first on Politico.