Edward V was 12 years old when he and his young brother Richard, Duke of York, went missing from the Tower of London in 1483. He was poised to inherit the throne from his father King Edward IV but, before his coronation, he was dubbed the product of an illegitimate marriage — meaning the crown was to pass over him. Richard III reigned for two years from 1483 to 1485, before being overthrown and killed by Henry Tudor, who became King Henry VII.

Henry allowed the rumours swirling about Richard murdering his own nephews to continue throughout his reign, as they served as propaganda which reinforced his position on the throne.

Then in the 17th Century, the remains of two small skeletons were found in the Tower of London, and were assumed to be that of Edward and Richard.

Preserved in an urn in Westminster Abbey, they have only been disturbed once in 1933.

Based on that brief examination, the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine speculated in 1994 that Edward V may have suffered from a condition called histiocytosis X, also known as Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis.

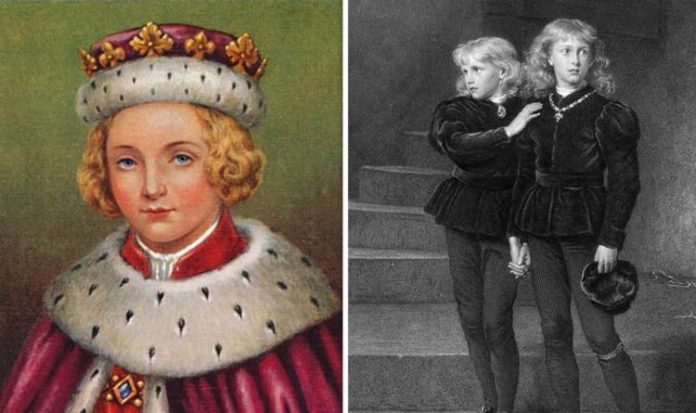

Edward V was one of the mysterious Princes in the Tower (Image: Getty)

The Princes in the Tower remain one of history’s greatest mysteries (Image: Getty)

An explanation of the disease on The Great Ormond Street Hospital website reads: “The immune system contains cells called histiocytes. Langerhans’ cells are a specific type of histiocyte that help fight infection in the skin.

“When a child has LCH, these cells spread through the bloodstream to other healthy parts of the body where they can cause damage.”

The condition has a much more positive prognosis now, and can be managed with treatments such as radiotherapy, surgery or chemotherapy.

However, the Royal Society of Medicine looked into whether it may have caused the death of Edward V during the medieval period, especially as it is more common in pre-pubescent boys.

READ MORE: Theory ‘Henry VIII was going stop Anne Boleyn’s execution’ uncovered

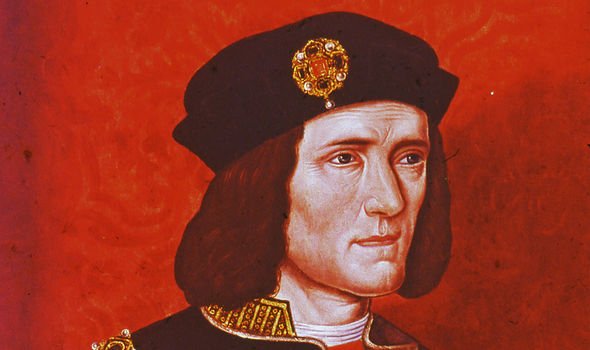

Medieval rumours claimed Richard III had them killed (Image: Getty)

The paper explained how one of the skeletal remains buried in Westminster Abbey had “congenitally absent” teeth.

Previous investigations also claimed that the remains showed an “extensive disease” which affected both sides of the lower jaw near the molar teeth and suggested it was chronic in nature.

The paper explained: “The gums would have been inflamed, swollen and septic, and doubtless associated with discomfort and irritability.”

This corresponds to patients with histiocytosis X.

The medical paper added: “The disease, unless it burns itself out, can be a progressively destructive condition which may prove fatal.”

Authors Dr A S Hargreaves and Dr R L MacLeod also explained: “It is quite possible that the surgeon did, in fact, remove the lower left first molar as a result of denudation of bony support, or because of local discomfort arising from secondary infection.

DON’T MISS

Queen Victoria first royal to carry disease which devastated family [INSIGHT]

Prince Philip’s late aunt created century-old unsolved mystery [EXPLAINED]

Why Queen refused DNA tests on remains of Princes in the Tower [EXPOSED]

The two princes were assumed to be dead after they vanished in 1483 (Image: Getty)

Richard III was the uncle of Edward V and Richard, Duke of York (Image: Getty)

“The general malaise that may accompany a multifocal form of histiocytosis X could well have contributed to the boy’s lowness of spirits, but cannot be held as solely responsible.”

But, they opine that “it may have weakened his resistance to other stresses”.

The paper reads: “There must always remain the possibility, though, that even if Edward had been crowned, he might not have survived beyond five years.”

The report suggests that pretenders during Henry VII’s reign often claimed to be Richard, Duke of York rather than Edward V, which could indicate there was knowledge of his poor health in the public sphere.

Edward was described as “weak and very sickly, as also was his brother”, by a contemporary, Sir George Buck, a historian who later served under Queen Elizabeth I.

He also believed Edward probably died while living in the Tower.

Henry VII’s reign saw the claims that Richard III was a murderer amplify (Image: Getty)

In his accounts from the time, Sir George added: “But whatsoever he died, I verily think that he died of a natural sickness and of infirmity.”

However, this account does counteract reports written by the physician who attended Edward V, John Argentine, which do not mention Edward being ill.

The paper also confirmed that the disease cannot be confirmed without the examination of soft tissue.

It concludes: “The observed extent of the disease would suggest that it was not the most likely primary cause of death.”

Westminster Abbey has rejected requests to examine the remains again with modern technology and carbon dating.