Brexit: Scottish Minister slams Royal Navy fisheries plans

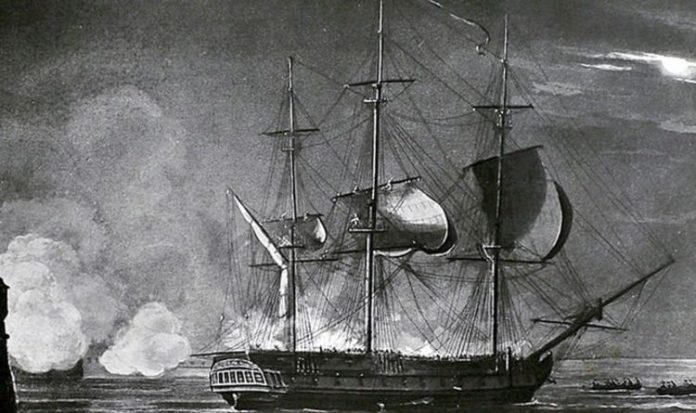

It was October 25, 1799, a good six years before the Battle of Trafalgar, when under cover of darkness the crew of the British frigate HMS Surprise rowed into a hostile harbour in small boats and captured the Spanish Santa Cecilia from her 400-strong crew. Despite imposing odds and vicious fighting, the British cut her anchor cables, lowered her sails and steered her from her berth as Spanish cannon shot fell around them. From start to finish, the expedition took less than an hour.

The battle ended with the captured Spanish frigate safely out of range of the fort’s big guns and brought alongside the Surprise, where her remaining crew welcomed their shipmates back with cheers of joy.

The operation remains one of the most dashing and glorious “cutting out” operations in Royal Navy history, certainly of the 1796-1808 Anglo-Spanish War, inspiring generations of navy-obsessed schoolboys as well as novelists like C S Forester and Patrick O’Brian.

The latter used the exploits of HMS Surprise as the basis for his best-selling novels – the 2003 film adaptation of which, Master and Commander, starred Russell Crowe as Captain Jack Aubrey.

But as Vice-Admiral Hyde Parker who ordered the operation said, it was, “As daring and as gallant an enterprise as is to be found in our naval annals.”

Sure, it was no great victory at sea like the subsequent Battle of Trafalgar, or Nelson’s other triumphs at Copenhagen, Cape St Vincent or the Battle of the Nile. Yet with the Government’s recent pledge to restore the Royal Navy to European preeminence with an extra £4billion a year for our armed forces, actions like this exemplify our nation’s proud maritime history.

The HMS Hermione’s crew mutinied while patrolling in the Caribbean (Image: Getty)

In fact, the cutting out of Santa Cecilia was typical of the scores, even hundreds, of small actions that took place during the Age of Nelson and helped contribute to the Royal Navy becoming the world’s most powerful naval force. What set this one apart though wasn’t just the fact it was fought at such long odds, or was such a spectacular success. It was because, for the Royal Navy, the stakes had been especially high.

The Santa Cecilia was a Spanish frigate which the British were especially keen to capture. It wasn’t money they were after – her decks weren’t filled with Spanish gold. Nor was she a particularly prestigious ship. This was about something far more important. The very pride of the Royal Navy had been threatened.

This operation marked a moment of sweet revenge. Just two years earlier, the Santa Cecilia was actually the British frigate HMS Hermione.

On September 21, 1797, while HMS Hermione was patrolling in the Caribbean, her crew mutinied, killing their captain and ten of his officers. Captain Hugh Pigot, had been a real tyrant – “a flogging captain”. He had a mercurial temper and, while discipline was often harsh, a brutal captain could make life a living hell.

Good men were broken by flogging, and bad ones were pushed to mutiny. Matters came to a head in mid-September, when Pigot ordered the flogging of Midshipman Casey. Not only was he innocent of the captain’s charge of carelessness, but everyone on board saw the beating of an officer as a shocking breach of the naval status quo.

A week later, during a squall, Pigot ordered a group of men aloft to reef the sails and, when they didn’t do it fast enough, swore to flog the last man down. In their haste, two young sailors slipped and fell to their deaths. Pigot merely ordered their bodies to be tossed overboard.

This callous act pushed the crew over the edge into mutiny. Most though, were kept in check by fear of what would happen if they rose in revolt.

Captain Hugh Pigot pushed his crew to mutiny (Image: Stratford Archive)

For a mutineer, there was no going back. There would be no return to family, wife or sweetheart. Instead they would be hunted for the rest of their life. It says a lot about conditions on board that so many were driven to step over that fateful line. It began late one night when, fuelled by stolen rum, a dozen armed men stormed the captain’s cabin.

They burst in, then stabbed and hacked at Pigot with axes and cutlasses. His blood-soaked body was thrown out of the cabin’s stern windows. Meanwhile another group rushed the officer-of-the-watch, cutting him down and also throwing his body over the side. So began an orgy of violence and drunkenness that continued long into the night.

One by one, most of the frigate’s other officers were hacked to death; two naval and one marine lieutenants, a midshipman, the surgeon, purser, carpenter, boatswain, gunner and captain’s clerk were all brutally murdered.

Only Midshipman Casey and one other officer survived the shocking bloodbath. It was the bloodiest mutiny in the Royal Navy’s long history – and when news of it reached London the British press and public were horrified.

HMS Surprise’s daring exploits in the Spanish Main helped inspire the film Master and Commander (Image: NC)

Meanwhile, the mutineers sailed to the port of La Guaria in what is now Venezuela, and handed Hermione over to the Spaniards in return for their freedom. As a French ally, Spain was at war with Britain, so they’d added treason to their list of crimes.

The Admiralty Lords were incensed, and, determined to bring the mutineers to justice, launched a decade-long manhunt. In the end, only 24 of the mutineers were ever caught and hanged for their crimes.

The rest stayed in Latin America, or made it to the United States, where they took on new identities. However, the Navy also wanted its ship back. By late 1799, they’d tracked her down to Puerto Cabello, also in modern-day Venezuela. She was now the Spanish frigate Santa Cecilia, and after two years of delay, was about to make her first voyage under the Spanish flag.

In Jamaica, Vice-Admiral Hyde Parker ordered Captain Edward Hamilton of the frigate Surprise to recapture her. That was why, on the night of October 25, Hamilton led his all-volunteer force in six ship’s boats into the harbour, and did exactly that.

In the jargon of Nelson’s time, this was a “cutting out expedition” – using small boats to capture an enemy ship at anchor.

Amazingly, despite the butcher’s bill of 119 Spaniards and the capture of the rest, not a single Briton was killed. The recapture of the Hermione thus ranks as probably the most dashing operation of its kind – a stunning victory.

Even more importantly, it was the perfect way for the Navy to right a terrible wrong.

The horrific orgy of murder that was the mutiny of the Hermione had been well and truly avenged.

To underline the point, the Admiralty renamed the ship HMS Retribution. So, in that pantheon of Britain’s naval heroes, and that long list of the Royal Navy’s triumphs, we should really add the name of Captain Edward Hamilton.

That October, in a remote Caribbean harbour, the most brilliant small boat action in the history of the Royal Navy was carried out in the truest traditions of the Senior Service. After the Navy’s bloodiest mutiny, this was a very public moment of sweet revenge.