He dedicated almost every waking hour he had to the little bear, even when he was off-duty. “He used to dream up the stories while he was mowing the grass,” his goddaughter, Caroline Bott, 80, says. “He lived with his disabled sister and elderly mother so his artwork was done late at night in his studio at the top of the house where he would literally burn the midnight oil.” This domestic image of Alfred at his home in Surrey could have come from a drawing straight out of Nutwood, with Mr Bear in the bespectacled artist’s place, waving off Rupert on another adventure.

So vivid and cinematic were his compositions, they had the power to make any imagined scenario believable.

“Each picture is a little work of art,” says Caroline. “He had to do two every day. It was jolly hard work and it used to take him about two hours to do each one.

He always did three because he could never have any time off otherwise.”

Alfred took on the Rupert Bear mantle after Mary Tourtel’s retirement in 1935.

Her last published cartoon was Rupert and Bill’s Seaside Holiday on June 27 and Alfred’s first strip, Rupert, Algy and the Smugglers, ran in the Daily Express the next day.

Then aged 43, the respected artist and cartoonist was a regular contributor to Punch and to society magazine Tatler but he was a Nutwood novice.

“I knew nothing of the subject so I bought the Daily Express, looked at Mary Tourtel’s work and drew three specimens keeping to her simplicity of line,” he said later in life.

Given just five weeks to plan his first story and pencil drawings, he thought “the strain was nearly too much” to take on.

“When Alfred was told he had to write the stories he thought, ‘Oh, well, I might manage a couple of them, and I’ll dry up’ but he said somehow they kept coming,” Caroline says.

Unlike Mary, who relied on her journalist husband Herbert to come up with the words, Alfred was a one-man Rupert operation.

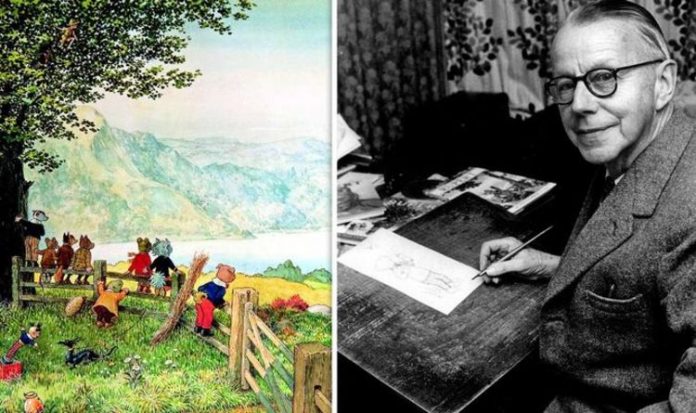

Rupert and Pals on long fence. Endpaper, Rupert Annual 1973, Rupert illustrator Alfred Bestall (Image: RUPERT BEAR © & TM Express Newspapers & DreamWorks Distribution Ltd/Caroline Bott)

Caroline remembers him as a lovely man. “He was important to me because I had no father,” the retired maths teacher says.

“He was an excellent godfather, there through all the important times in my life.”

Her father Frank was killed in World War Two and before his death, asked Bestall, his cousin, to become Caroline’s godparent.

“He took me to my first concert, which was the Nutcracker Suite, and then I asked him if we could go to a purely orchestral one so we did,” she recalls.

So influenced was she by Alfred’s love of music, she saved up for a gramophone.

“He thoroughly approved of that,” Caroline recalls, “and in-between birthdays and Christmas, which he never forgot, he would often send me the odd ten bob towards it.”

Though he always made time for her, Alfred’s life was first and foremost dedicated to Rupert.

His arrival marked the introduction of the double-frame format, and this saw Bestall introducing stronger narratives and cliffhanger stories.

Rupert Bear and Raggety (Image: RUPERT BEAR © & TM Express Newspapers & DreamWorks Distribution Limited. All rights reserved.)

In an interview with the late Monty Python Terry Jones, Alfred once stated he wanted to put “a bit more action and a lot more humour” into the stories.

Rupert and the Goblin Cobbler, in which Mrs Bear can’t stop dancing because of a new pair of slippers, was one wonderful example.

Caroline says this humour was always evident in his interactions with people, despite his notorious shyness due to a severe stammer.

“He broke his hip at the age of 90 playing table tennis with my daughter and when the chaplain visited him in hospital, he said, ‘I was only sorry I didn’t return the shot’,” she laughs.

When the Express Children’s Editor Stanley Johnson hired Alfred, he had one strict instruction – “no evil characters, fairies or magic”.

Mary Tourtel, especially after her husband’s death, tended towards the macabre in her work.

She also employed magic as a fallback to whisk Rupert home out of any tight fix. To counter this, Alfred used technology and inventions.

His second story, Rupert’s Autumn Adventure, which ran from August 30 until October 31 of 1935, contains a machine belonging to The Professor that can turn leaves into gold.

When it is stolen, Rupert must rescue his friend Barbara by aeroplane before the pair parachute home.

But the changes he made were subtle. “He knew he had to change him imperceptibly,” says Caroline. “A big part of it was that he was good at science.”

Frog Chorus. Endpaper. Rupert Annual 1958 (Image: RUPERT BEAR © & TM Express Newspapers & DreamWorks Distribution Ltd/Caroline Bott)

Alfred was born in 1892 in Mandalay in Myanmar, formerly Burma, to two Methodist missionaries.

He and his younger sister Maisie, then aged two, returned to England in 1897 while their parents stayed abroad.

The children moved between relatives and their father’s Methodist colleagues until their parents returned in 1910.

Alfred attended public school in Colwyn Bay, sparking a lifelong love of north Wales. At school he excelled at drawing but, Caroline says, he was encouraged to join the Civil Service because at the time it was considered “respectable rather than art”.

Thankfully, he followed his heart, winning a scholarship to Birmingham Central School of Art before serving in the First World War. But he still made time for drawing.

“Alfred’s father managed to acquire pen and ink and paper for him so he was able to do drawings for Blighty, the army magazine,” Caroline says.

After the war he did some illustrations for Enid Blyton before working for Punch and Tatler. In need of more regular work, he applied for the role of Rupert illustrator in 1935.

“He saw it as a terribly responsible job because he knew he could influence the minds of children,” Caroline says.

“There were one or two members of our family who, because of the pictures he had exhibited in the Royal Academy, thought it was a travesty of his art, but he didn’t see it like that.”

She saw more of him after her marriage when she moved to Godalming, Surrey, near Alfred’s home in Surbiton. Together with

her three young children, they would often stay at his cottage in Beddgelert, North Wales, which he bought in 1956 and lived in permanently from 1980 onwards.

“He would lend us his home and sleep in a bed and breakfast down the road,” Caroline remembers. “He would join us for picnics and so on, and I would cook supper.”

Alfred Bestall was aged 90 when he drew this picture of Rupert Bear with a mic (Image: Caroline Bott)

Alfred enjoyed the company of children, especially if they were Rupert fans.

In 1947, Beryl Sweet, Pauline Coates and Janet Francksen, wearing their uniforms of the 10th Surbiton Guides, accosted him on his doorstep begging to be put in a Rupert cartoon. He duly obliged, even putting in Beryl’s cat Dinky.

“He loved children. And, of course, they loved him,” Caroline says. The lifelong bachelor, who had one romantic relationship in his youth, was once asked if he regretted not having children.

“Not really,” he replied. “I feel as if I’ve had thousands of them.”

As for his lush drawings of Nutwood, although Alfred would never reveal its exact inspiration, Caroline believes it was his homes in Surrey and Wales, plus the drive through the Cotswolds between the two.

“The Rupert and the Long Fence endpapers in the 1973 annual [the inside front and back pages] with all the pals leaning on the fence and looking at the lake is a place I know well,” she says.

Alfred retired from drawing the Daily Express strips in 1965 at the age of 73. He had created 273 Rupert stories in all and, incredibly, never even signed his work for the first 12 years out of respect for Mary until her death. He continued to draw for the Annuals until 1983.

Two years later he was awarded an MBE in 1985 but was too ill to receive it in person as he had developed cancer. Shortly before his death on January 15, 1986 he was visited by Caroline in hospital, where he doodled his last Rupert artwork on an envelope.

“You had better have Penlan [the Welsh cottage],” he said. “You’ll find all my early artwork in the loft. You’ll have to have a bonfire.” Caroline believes he was being quite serious. “He was a modest man,” she says. “He never thought that anybody would value his early artwork.”

Daily Express readers and Rupert Bear fans know different.